|

| Start Reading. I've read this book more times than I can count. I've also watched every instructional/clip known to man about this throw. |

This post may seem disorganized, but I will do my best to tie it all together coherently.

When I started Judo, as a lightweight, the shoulder throw was my throw of choice. Well, that's not entirely accurate. My first coach was a shoulder throw expert and therefore, I was destined to spend most of my time with him honing that.

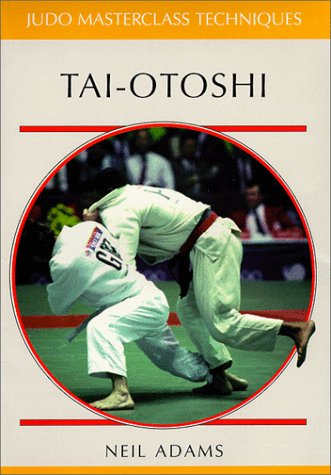

A knee injury forced me to abandon the throw for quite awhile and as I switched clubs, I chose Tai Otoshi as my next tokui waza, meaning "pet technique". That is, the throw around which you build most if not virtually all of your standing/throwing game.

Tai Otoshi is a "te waza" or hand technique: meaning that the majority of what makes it work is precision and timing and direction with the hands. The usage of the legs and hip is different from hip throws or foot sweeps in that the only points of contact I have with my opponent are my 2 grips and the brief moment when his shin may hit the back of my leg/calf.

It is a difficult throw for these reasons.

Here I am from about 4 years ago in a local tournament winning by Ippon with my throw of choice: Tai Otoshi - yes, I'm aware in the video it comes off as more of a seio otoshi/type throw, but save the semantics for another day.

And here is another throw for Ippon from the same day 4 years ago, this time a cross grip version to address my opponent's movement:

At any rate, I had asked my first coach what was a throw that had a very tough fall to take/was devastating in competition, and worked regardless of size. Tai Otoshi was his answer.

So, for the next 3-4 years I relentlessly worked at it in the clubs where I trained and practiced.

It's not always so important what throw you choose, only that you commit to doing your very best to approach some level of deeper understanding of the throw, and to know that it will take years to do so.

It took me 3-4 years before the tournament above where I actually used it in competition.

And one day, after getting blocked, stuffed, countered for years on end by everyone, I won 3 matches with it (and it could have been four, but the referee didn't award the throw).

Just like you hear people say, "it just clicked". I had hit the point of deeper understanding that it had become almost completely automatic. It took between 3 and 4 years for it to work a handful of times in one day of competition.

Here is the 3rd Ippon by Tai Otoshi from that day:

Before I hurt my knee, I would routinely during competition season for Judo do 300-500 uchikomis on my own at night or in the morning with some old tire tubes tied together ala this:

for the shoulder throw. The debate rages on about the efficacy of what is called static uchikomis, but I fundamentally believe for solitary practice, they are a great tool.

At any rate, you can imagine anywhere from 300-500 repetitions a day across months out of the year, plus the time in class gets one toward the 10,000 hour/repetition rule.

I recently read Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell, and it espouses this 10,000 hour/repetition rule.

What is the 10,000 hour/repetition rule? The rule is the estimate as to the amount of time spent invested in an activity/movement/et cetera required to approach some level of deeper understanding/mastery.

How does one go about doing this?

Go to class. Have your instructor critique your basic motions/motor skills for the throw.

Then, over time, you start pinpointing finer points to address.You will also pick up variations in gripping and set ups (different foot sweeps or foot work to get into optimal throwing position).

Then, over time, you start pinpointing how it works against defensive posture, foot sweeps to open up their defensive or stiff arm posture, and how it works against different body types.

Then, the time comes to test it in tournaments (this can begin any time during the above process).

Be prepared to fail. See very failure as one step closer to the goal.

In Jiu-Jitsu, missing the window or failing to execute properly doesn't necessarily immediately end the match. Missing the window to throw, or getting countered by better players in practice symbolically means you lost the match and your tournament day would likely be over.

You were countered and thrown. For this reason, the right mindset in training is to set aside your ego and simply devote yourself to the process. There is little place for pride or vanity in training. It is only an impediment to success. If you fear being thrown you will never attempt the throw enough times and against enough better, more skilled players to develop the timing, precision, control, and instinct for the throw.

The only reason why I do Tai Otoshi with confidence now is the thousands upon thousands of times I did it incorrectly or at the wrong time and gradually found the right feeling, the right sense of timing for when to execute.

The old adage about Edison's 10,000 failed tries to create the filament/light bulb proves apropos. Often, learning the right way is a process of elimination more than any other factor. I eliminate all the wrong ways to do something and arrive at the right way simply by process of elimination. It's not sexy. It's not pretty. It's not fun. And it takes time as well as the willingness to grind through all the plateaus in learning to execute this one throw. You have to see past the leaves, past the dirt, past the rocks, and see the forest you are planting each time you try and fail.

Why does it take roughly 10 years to get a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt?

That's about 10,000 hours. This of course changes some with natural ability and those that train full-time throughout the year as they get in those 10,000 hours sooner than the average practitioner.

I've spent the past 7-8 years working on Tai Otoshi. That does not make me an expert, but it is the beginning of understanding it. I've logged more hours than I can count doing uchikomis, in practice, getting countered, missing the opening, and that...is why I've found some moderate success with the throw. I've asked almost every black belt I know how they understand the throw, any variations they know, and how they were taught the throw. I've sought out every single piece of information there is that I can get my hands on regarding this one throw. This tireless desire to understand at the deepest level this one throw and how/why/what makes it work is the kind of precision of focus necessary to master something. Before the Pan-Ams I spent the vast majority of my time other than Open Mat drilling the takedown to top position to passing the guard. For months on end, with every person I trained with regardless of size or skill level.

Go start grinding.

The fourth (almost) Tai Otoshi of the day, the one that got away:

No comments:

Post a Comment